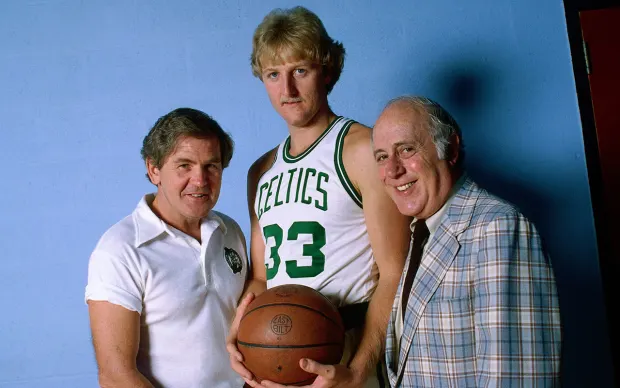

After touring the Hall of Fame for professional basketball in Springfield, Massachusetts, Larry Bird, the self-proclaimed “Designated Savior” of the sport, was transported back to Boston. Driving the gray Cadillac Fleetwood was agent Bob Woolf, who arranged for Bird to sign a five-year deal with the Celtics that would pay $650,000 a year plus an estimated $325,000 signing bonus. As the highest-paid rookie deal in NBA history, Bird’s is equal to or greater than that of senior players David Thompson in Denver, Bill Walton in San Diego, Moses Malone in Houston, and Artis Gilmore in Chicago. With a sidelong glance at the $3.6 million man, Woolf remarked, “You better be good.”

“I’ll kill ’em,” answered Bird.

“But what if you don’t?”

“Everyone will then exclaim, ‘It’s amazing what might have happened to him. “He did a great job in college.”

And they both started laughing. Why not? The NBA and the Celtics have crossed fingers; Bird and Woolf have the money.

Bird’s performance on the court will be viewed as a massive failure if he falls short of being magnificent. There has never been this much interest in a single player—yes, uncontrolled hope—since Walton entered the NBA in 1974. Shrugging his shoulders, Bird says, “Nobody expects much of a rookie.” False. According to Bill Fitch, Boston’s new coach, “I’d say he adds a little to our expectations.” Well, Bill, hurry up.

Similar to Walton, Bird is a highly promising player coming out of college, but that isn’t the only thing driving the buzz in the pros. The main reason for all the commotion is that, similar to Walton, Bird is white, yet the majority of NBA rosters are black. Those who believe that the color of the players has a significant impact on whether or not spectators show up and pay attention hope that Bird will force them to do both in greater quantities. Still, some, including Bird, believe that the NBA’s seemingly declining reputation has nothing to do with a lack of Great White Hopes.

Yes, but Bird won’t be too good if the guys he’s passing to are hurling bricks.

– null

He says, “I understand why people don’t enjoy watching professional basketball. “Neither do I. It’s not thrilling. It’s also vintage Bird, if that makes many at league headquarters squirm. He’s a straight shooter (28.6 points per game last year at Indiana State, when he was named College Player of the Year), he speaks clearly (“Very few people can turn a team around by themselves, and I’m not one of them”), and most importantly, he passes the ball. In fact, the best ball handler in league history, Bob Cousy, remarks, “He has exceptional passing ability, the best I’ve ever seen.” However, Fitch issues a warning: “Yeah, but Bird won’t be too good if the guys he’s passing to are throwing up bricks.”

Talk of Walton’s potential signing with San Diego (see page 102) and the ensuing discussion regarding Portland, Walton’s former team, and its compensation made for a lot of news during the off-season (both months of it). However, there was also a lot of discussion about the signings and talks between Bird and another rookie on the left coast, 20-year-old Earvin (Magic) Johnson of Michigan State, who is currently a member of the Los Angeles Lakers. “To be honest, it has been hard for me to understand how the Lakers could lose with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,” says former UCLA coach John Wooden. They ought to have won without the use of magic. They will undoubtedly with him.